RESUMEN

Análisis de los principios de las metodologías activas siguiendo las orientaciones e instrucciones propuestas por la legislación nacional y autonómica de la Región de Murcia. Especificación de los condicionantes que posibilitan que el aprendizaje activo se produzca de acuerdo con las investigaciones de los expertos en la materia.

Under the Order 3rd June 2016, the Ministry of Education of the Region of Murcia put forward a set of instructions and regulations for the teaching of a Foreign Language in this Autonomous Community. Hence, it asserts that linguistic diversity is an undeniable reality which makes the Communicative Competence to be fostered as a key priority. Even more, the Region of Murcia foresees a strategy known as ‘+ Idiomas’ (‘+ Languages’) by which both schools and high schools are to gradually become bilingual or plurilingual. Furthermore, this legislation together with the Royal Decree 1105/2014, which establishes the basic curriculum for Compulsory Secondary Education and Baccalaureate, and the Decree 220/2015, the Curriculum for the Region of Murcia, highlight the use of Active Methodologies as the most suitable means to reach the goal of a real Communicative Competence. However, what is an Active Methodology?

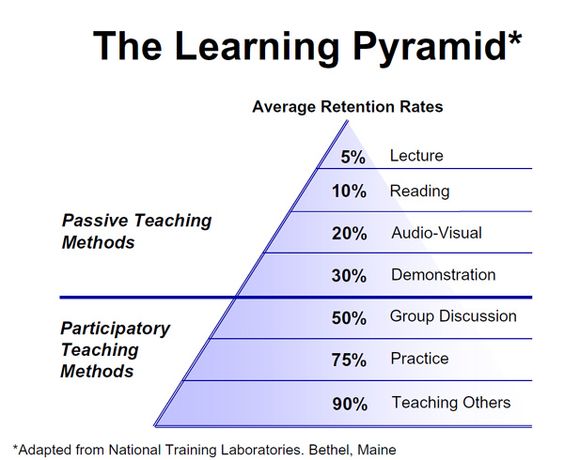

Active Methodology derives from the term ‘active learning’, which was defined by Bonwell and Eison (1991) as ‘any instructional method that engages students in the learning process’, that is to say, active learning techniques requires students to do meaningful learning activities, think about what they are doing while taking hold of their own learning process. Therefore, it can be deduced that for students to learn they must do more than just listen and, what is more, they must engage in higher-order thinking tasks such as analysis, synthesis and evaluation of their own learning to be aware of the strategies used to reach any specific knowledge, this leading to lifelong learning and autonomy. By the same token, the Seven Key Competences encouraged by the cited legislation, and more specifically the Learning to Learn and Sense of Initiative and Entrepreneurship Competences are naturally exercised through this type of methodology.

No doubt active learning classrooms require different planning and teaching strategies than traditional classrooms and, even more, they are to depart from four basis steps, to wit: first, having a clear learning goal; second, using multiple pedagogies to cater to our students’ interests and needs; third, leveraging digital and analogue tools; and fourth, increasing access and communication among instructor and learners.

Likewise, Barnes (1989) suggested a list of principles for the active learning to occur, namely:

- Purposive:the relevance of the task to the students’ concerns.

- Reflective:students’ reflection on the meaning of what is learned.

- Negotiated:negotiation of goals and methods of learning between students and teachers.

- Critical:students appreciate different ways and means of learning the content.

- Complex:students compare learning tasks with complexities existing in real life and making reflective analysis.

- Situation-driven:the need of the situation is considered in order to establish learning tasks.

- Engaged:real life tasks are reflected in the activities conducted for learning.

Besides and following Grabinger and Dunlap (2015), the characteristics of a learning environment in tune with active learning are:

- Aligned with constructivist strategies.

- Promoting research-based learning with authentic real content.

- Encouraging leadership skills of the students through self-development activities.

- Creating an atmosphere suitable for collaborative learning for building knowledgeable learning communities.

- Cultivating a dynamic environment through interdisciplinary learning and generating high-profile activities for a better learning experience.

- Integration of prior with new knowledge to incur a rich structure of knowledge among the students.

- Task-based performance enhancement by giving the students a realistic practical sense of the subject matter learnt in the classroom.

Bearing the previous consideration in mind, examples of ‘active’ activities include working with varied groupings for discussion, debates, think-pair-share activities, short written exercises and even submit the class interaction rules to students’ polling (Bonwell and Eison, 1991). Additionally, it is worth noting that a class discussion may be held in an online environment too, whose interactions would have to be modulated by the teacher, who may offer well-closure topics for the students not to stray.

Bibliography

- Spanish Ministry of Education, Royal Decree 1105/2014, 26th December, asserting the basic National Curriculum.

- Ministry of Education of the Region of Murcia, Decree 220/2015, 2nd September, ascertaining the Curriculum for the autonomous region.

- Ministry of Education of the Region of Murcia, Order 3rd June 2016 about the teaching of Foreign Languages.

- BARNES, D. (1989) Active Learning. Leeds University TVEI Support Project, 1989. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-872364-00-1.

- BONWELL, C.; EISON, J. (1991). Active Learning: Creating Excitement in the Classroom. Information Analyses – ERIC Clearinghouse Products (071). p. 3. ISBN 1-878380-08-7. ISSN 0884-0040.

- ED340272 Sep 91 Active Learning: Creating Excitement in the Classroom. ERIC Digest. ERIC Clearinghouse on Higher Education, Washington, D.C.; George Washington Univ., Washington, D.C.

- Grabinger, R. S. & Dunlap, J.C. «Rich environments for active learning: a definition». Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- Panitz, T. (1999). Collaborative versus Cooperative Learning – A Comparison of the two Concepts which will Help us Understand the Underlying Nature of Interactive Learning. Eric. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

María José Moreno Martín